Fascinating discussion of photographing, tweeting, and generally sharing results at conference presentations.

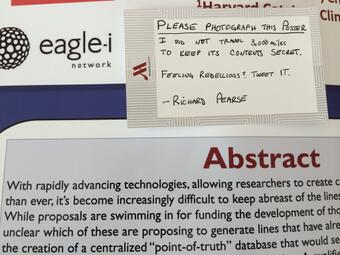

Apparently, the International Society of Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) prohibits photo-taking of posters and talks, as do most other societies. Moreover, they tried to suggest a policy for Tweeting - "okay for general findings but not for pics or data."

I find it strange that someone can share with an audience of 3,000 at a conference, but be disrespected by an excited tweet of his or her results. Couldn't the people seeing it on Twitter also be in the audience? Or does the presenter tailor their message depending on the full list of attendees?

I don't need to discuss this any more here because Alexey Bersenev did a terrific job on his blog. Go read his article!

The only thing I will add is that I am convinced people overestimate the threat of being scooped. Does it happen? Of course! Does it happen because you presented at a conference? Probably not (at least in molecular biology). We scoop each other inadvertently. Lots of researchers, studying questions of the day, with the tools/techniques available that day. Of course, just by chance, many will do the same thing. If anything, I am sure presenting, talking, and sharing as much as possible can only reduce the chance of being scooped. You are more likely to learn of others doing this and collaborate. You are more likely to inhibit others from doing this, just because they know you have been working on it for a year now. And even if 5% of the time talking about your work leads to being scooped, but 70% it prevents scooping, as scientists, we should be able to determine which makes more sense.

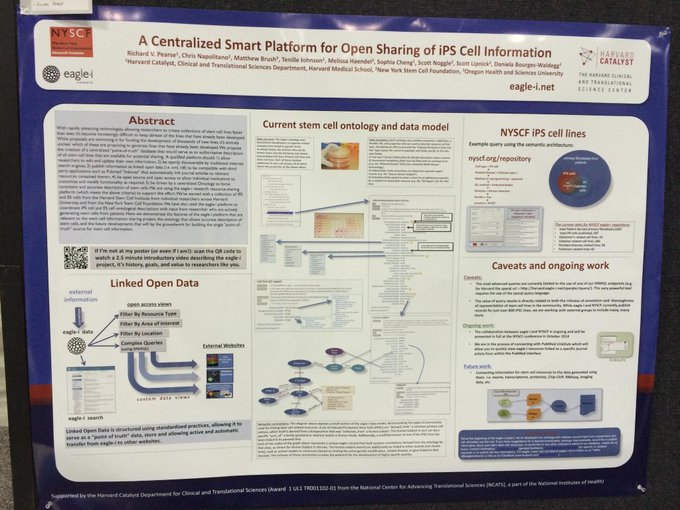

And the poster itself!!!!!

COMMENT